Elly Anderson (nee Van Der Sommen)

In my small collection of Dutch books at our home in South Australia there is a 1950 hard cover publication titled Australië – Land van Vele Mogelijkheden by J.J. van der Laan. It was one of many books that my parents brought to Australia when they emigrated from The Netherlands after World War II.

Translated, the title suggests that Australia was a land of many possibilities. Farmers and labourers had good prospects in Australia, according to the author, but as I reflect on the experiences of my parents and their five children, it seems to me that, for others, possibilities probably did outweigh real opportunities in the early 1950s.

My parents, Gérard and Maria van der Sommen, owned a drogisterij, a Dutch style chemist shop in the provincial textile town of Helmond in southern province of Noord Brabant. World War II and its aftermath were a major factor in their decision to emigrate. My mother was German-born and in earlier years, as a young woman, she had enjoyed happy and carefree holidays with relatives in Helmond. That was when they had met. My father was a third-generation Helmonder and his family were local business people.

They had been married for just over three years, had two very young children and their shop in the main street was flourishing when, in May 1940, they were dismayed to find their two countries at war with each other. Like the rest of the community, they existed as best they could under German occupation and rejoiced when the town was liberated by the Allies in September 1944. But this joy was greatly marred due to my mother’s origins, when they became the target of anti-German sentiments.

Graffiti was removable but the business, on the other hand, became so adversely affected, joining the general exodus for Australia seemed then to be a good option. Their bookkeeper had also neglected his duties during the war years and the huge tax bill that resulted was the final death knell for the chemist shop. The premises, including our upstairs home, were duly sold and converted into a van Haren shoe store by new owners.

The author J.J. van der Laan, warned readers of his book that emigrating was a serious business, breaking off ties and tearing loose one’s roots. It was something of which my mother especially was only too aware and the decision was made with caution and also with reservations on her part. This meant that my father would go first and my mother and we children moved in with grandparents – and so, as a family, we were split three ways for a whole year.

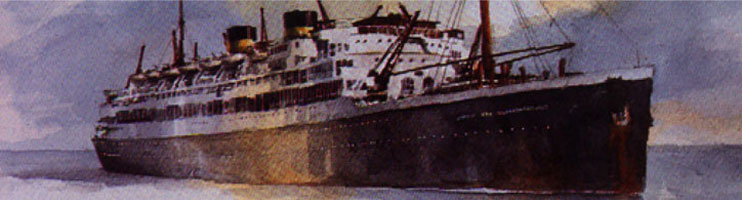

My father, then aged 30, sailed from Rotterdam on the R.M.S Orontes on 26 April 1950. As it happened, his departure coincided with the death of my maternal grandfather and so my mother had the double heartache of first saying goodbye to her husband at the wharf and then attending her father’s funeral in Germany. How great her grief must have been.

The two younger ones, Frans Joseph and Rose-Marie, remained in her care in Germany, while my older sister Gonny and I continued to live in Helmond for the next 12 months. In Germany they soon settled into their new environment and learnt a new language from cousins, school and kindergarten. One day they sent their father a message in a helium-filled balloon, although they had no idea how far away Australia was.

Melbourne was my father’s first Australian destination and there he lived in single men’s quarters and reconnected with other Helmonders, at least 20 of them, who had also made the move. Even though he experienced loneliness and missed us all, his airmail letters home were full of optimism and hope as he searched for suitable family accommodation and attempted various types of work possibilities that keyed into his expertise. At one stage he wrote about a job he had obtained with the face care products manufacturer Pond’s.

Even though we were a close-knit extended family in Helmond and also had some good playmates, as an 11-year-old I was excited about the idea of going to Australia. On 2nd February 1951 I was proud to receive a telegram from my father, worded in English, wishing me a happy birthday and promising me that the next one would be in Australia. I was so impressed that he had signed off as “Dad”.

Housing, especially for families, was as big a problem in Australia as it was in The Netherlands in 1950 according to the author J.J. van der Laan and this was indeed my father’s experience in Melbourne. In his own words, landlords did not want to know him because he had four children. After looking at various options, even contemplating work in a lead mine in Queensland to earn enough to build a home, my father was persuaded by a fellow Dutchman to try his luck across the border in Mount Gambier, in the South East of South Australia.

The Mount Gambier region was known for its pine plantations but it also had a thriving limestone industry and at first my father tried his hand at cutting stone in the quarries. His accommodation was a caravan at this time. But the work was physically too demanding and he was soon looking at other possibilities. In view of the housing shortage at that time he clearly saw a future in the building industry and so his next venture was making roof tiles.

After living in a guest house in the town and then at the home of a local bank manager and his wife, a kind and hospitable couple, my father was offered a large house on the outskirts of the town by the Parish Priest. There were sheds on the property and this is where he set up his two-man factory, Mount Gambier Tile Works. He was now ready to send for his family.

He wrote to us about the school we would attend and told us we’d be wearing a grey tunic, white shirt and striped tie. This was fascinating, as school uniforms were unknown to us in Helmond.

I was intrigued to hear about the vast oceans on which we would be travelling to Australia. Until then the largest expanse of water I had seen was the canal at the end of our street and my only world had been our neighbourhood. I was too young to realise then how I would miss this familiar world, especially our relatives and friends, although we would do our best to fit into our totally new environment. I would envy talk among the girls at our new school about their cousins, aunts and uncles. My home and immediate family would become very important for me.

Before our departure my fifth class school teacher in Helmond arranged for my classmates to give me a Dutch-English/English-Dutch pocket dictionary, bearing their names inside the cover. This dictionary was very precious to me and would prove to be most useful in Australia, also for my father who referred to it frequently.

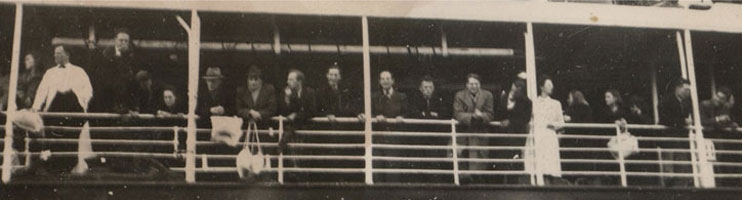

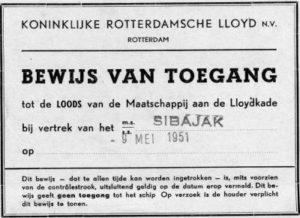

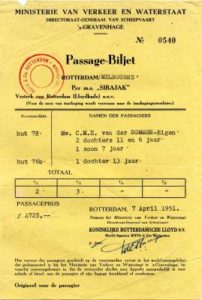

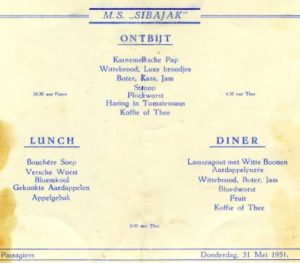

On my father’s advice, we would bring as much of our furniture and belongings as possible. So when we departed on the M.S. Sibajak from Rotterdam on 9 May 1951 we left with 13 cubic metres of furniture etc., tightly packed in a wooden crate, as well as seven suitcases plus various school and hand bags. My mother remarked in a letter that we could not possibly have brought any more but some belongings had still been left behind. As it turned out some of crate’s contents, such as bikes and chairs, had been pulled apart to maximise packing space and these were found to be incomplete on arrival, but after some inquiries the remainder would follow in due course. The cost of our passage was fl.4725 (Dutch guilders) and the freight cost totalled fl.1284.15.

My father had warned my mother to be watchful of the little ones, as it was easy for them to become lost on such a large ship. Her shopping list before our departure included salt water soap and tablets for motion sickness.

Relatives saw us off at the docks. How they felt I do not know but the correspondence and gift parcels that ensued in the following years were a sign that our bond always remained strong.

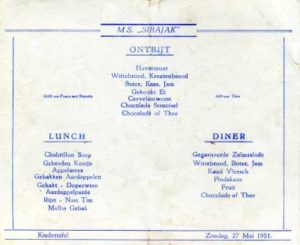

My younger siblings and I shared a cabin with our mother and my older sister was accommodated with people next door. Our route would be via the English Channel, the stormy Bay of Biscay, the Straits of Gibraltar where I photographed the Rock with my new Box Brownie camera, Suez Canal, the sweltering Red Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Great Australian Bight. Our ports of call were Port Said, Aden, Colombo, Fremantle and Melbourne.

Not long before our departure there had been an outbreak of smallpox in The Netherlands, originating in Tilburg (not very far from Helmond) from where, because of the risk of infection, an aunt could only say goodbye to us by telephone. Immunisation of all ship passengers was compulsory. There were some very red and swollen arms on the decks during that time. My younger siblings and I had already received our needle before departure, unlike my older sister who would have been at risk of complications. She was required to receive hers on board and was very ill for a time.

Throughout the voyage a daily news bulletin, the “Nautical Information Service”, was broadcast through loudspeakers on the decks, always preceded by the marching tune “Star and Stripes Forever”. For me, hearing this tune in future times would always bring back the memory of that voyage. The bulletin was available in print at the end of our trip, with proceeds going to the Princess Margriet Fund to aid thousands of war widows and orphans linked to the Dutch Merchant Navy. It was only six years since the end of the War. I was too young to appreciate all its implications and consequences but the bulletin that is now in our memorabilia has since made for some interesting reading.

It relates that thousands of Dutchmen lost their lives at sea. It occurs to me now that my father might well have been one of them early during the war, had he, together with a military party from Helmond, boarded an England-bound ship in France. The ship was bombed in the harbour in Bologne and a number of men were killed. But my father had been deployed en route to France to drive an ambulance of injured marines and had then been taken prisoner of war for a time.

The 24-year-old Sibajak itself was also a war ship and its company, the Rotterdamsche Lloyd, alone lost 400 personnel among its seafarers.

Early in the voyage there were reminders of those terrible years. The minefields in the English Channel had not been cleared at that stage; the sighting of Normandy brought back memories of the D Day invasion of 6 June 1944 and the tragic sinking, only a month before our voyage, of the British submarine the Affray. Attention was also drawn to British war ships off Gibraltar and to Malta’s capital La Valetta, rising from its war ruins. Off Greece the Gulf of Nauplia was the resting place of the ship Slamat, a pre-war sister ship of the Sibajak, which had been sunk in 1941.

Our voyage seemed long and tedious, probably because I was seasick for much of the time. Even the children’s farewell party with its amazing array of decorated cakes could not arouse my interest when we reached Fremantle. Disembarking briefly to visit Cairo was a welcome relief and the crossing of the equator, with a visit from King Nepture and the unceremonious covering with what looked like green soap of some of the people who were crossing for the first time, was an entertaining distraction and so were the flying fish that occasionally rose above the surface of the water. On 1 June an Asian crew member went missing overboard. His sandals were found by the railings in the morning. The ship retraced its course in a futile search for him and left behind a life buoy with a bright white light before moving on.

On about 14 June 1951 we were met in Melbourne by my father and two Australian friends who had driven their cars there to transport us and our luggage the 500km to Mount Gambier. Because I had lost a lot of weight on the voyage, it was decided that I should fly with my father instead. In Melbourne he followed my mother’s instructions to give me some milk as soon as possible and thus I experienced my first Australian banana milkshake. It was more than I could consume but also rather nice.

The novelty of my first plane trip had hardly worn off when I found myself seated with my father and some of the luggage on the back of a horse-drawn dray for our 3km journey via the main street to our new home in Mount Gambier, in due course to be joined by the rest of the family.

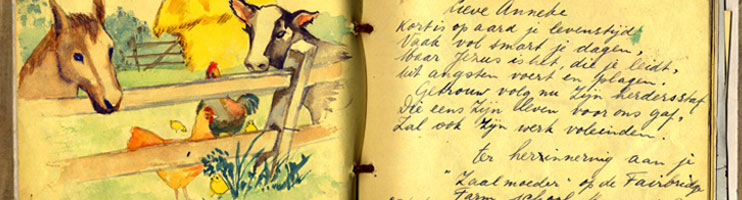

With the furniture yet to arrive, my sisters and I were immediately whisked off to the local Mercy convent boarding school where we would remain for several weeks. In spite of a friendly reception from the nuns and boarders at Mater Christi College, it was a disconcerting situation for us. My pyjamas had been hastily wrapped in some pages of an old Dutch trade magazine and I found it strangely comforting to read these in my bed whilst tucked up under the blankets, simply because the words looked familiar.

But we soon settled in and also began to learn a few words of English. I thought that the ‘th’ sound in the English language was very strange. There would be blunders of course and these became the source of much amusement in later years. For instance, in her English test my sister thought that the feminine form of ‘monk’ was ‘monkey’ and when I went to the butcher one day to buy six kidneys for my mother I asked for ‘six kittens’.

At my father’s suggestion, our names were anglicised where possible in order to fit in. He himself was already known as Gerald and I changed from Elly to my baptismal name, Elisabeth. Frans Joseph became Francis and then Frank. At times our surname was difficult for some locals and more than once it was confused with someone else’s Dutch name. Later on my brother saw our name as a real drawback and considered modifying it to improve his chances of work promotion.

In school we initially just sat at our desks and observed and listened. One day my sister and I were invited to perform a Dutch dance in the classroom. The nuns must have known that back in Helmond we had attended dance school. In boarding school during those first few weeks we slept in a dormitory and ate our meals in a large dining room while one of the boarders or nuns sat in a corner to share a reading from the Scriptures. The meals did not seem very different but I did think that pumpkin was a strange looking vegetable. One of the nuns occasionally liked to spoil us with treats of coconut ice. I remember often being called “good girl” but had no idea what this meant.

The Victorian style limestone and dolomite house which my parents leased from the Catholic Church had six bedrooms, a large central dining room and a spacious kitchen. In the first few years we shared it with other Dutch migrant families still looking for a home. Later my parents took in boarders to supplement their income.

There was a milking shed in our back yard and there were cows and calves grazing in the surrounding paddocks. Eventually we realised that we were able to buy fresh creamy milk in a billy can from the dairy farmer, Mr Best, and we also picked large field mushrooms for some of our meals. We children helped Mr Best distribute hay around the paddocks from the back of his utility, we climbed haystacks and hedges and built a fort in a large fallen pine tree some distance from the house. For my younger sister and brother there was even some clandestine horse riding.

It was all very different, compared to our childhood days in Helmond, but children will be children, as the saying goes.

My sister Gonny found some continuity of her former life through the Girl Guides movement, of which she had also been a member in Helmond.

Christmas and St Nicholas celebrations remained a joyous part of our lives, in both the Dutch and German traditions.

In our house all heating was wood-fuelled, with a copper in the laundry and a chip heater in the bathroom, a woodstove with a rather smoky chimney in the kitchen and open hearths in all the rooms. We all took our turns in the task of sawing up fire wood. Equipped with a bow saw and a wood horse, we cut up the pine off-cuts as they were required.

The fireplace in the dining-cum-living room became a focal point in our lives. We sat around it to keep warm, toasted bread on long forks, listened to the radio and played board games. When my mother could not get enough draught for the kitchen stove she cooked the potatoes on the fire as well.

Once in a while a visitor would pull up another chair – an Irishman with a fine tenor voice brought over by Father Murphy, a Dutchman passing through who entertained us with his ukulele and impromptu songs, the St Vincent de Paul men who led us in the Rosary after both our grandmothers had died within a month of each other and some Dutch journalists seeking a migrant’s story.

The house was eventually purchased by my parents and it would remain our family home for the rest of their lives.

Soon after we came to Mount Gambier my mother obtained a job teaching physical education at our school. At home she would practise her instructions in English with us as her pupils. “Breeze in, breeze out” she would say as we lifted and lowered our arms in unison out on the front lawn. She taught PE (Physical Education) for two years until there was another baby on the way. Our youngest, Patrick, was born in September 1953.

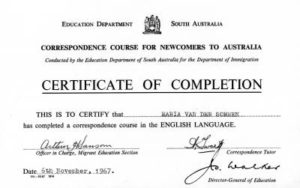

She worked on improving her English and later, to ensure that she would be able to communicate with her grandchildren in the future, she also took up a correspondence course for newcomers with the Education Department. Along with a certificate there was a letter from the Migrant Education Officer, congratulating her on completing the course and encouraging her to practise her English at every opportunity.

As for my father’s working life, he sold his roof tile factory after two years and then worked in cheese factories for some time, obtaining a certificate in Dairy Technology at the local Technical school. After that he sold electrical goods in a shop and as a travelling salesman, and later he was storeman at a nearby timber mill. The lack of opportunity in his own profession was disappointing for him.

For his offspring he hoped for better prospects. My older sister and I left school after three years of secondary education, as was normal then. Gonny had done well at school and obtained a clerical job with a local firm. She and her husband Joseph and their family lived and worked at the rocket range desert town of Woomera in South Australian for some years and later went into business in the Adelaide area. The last of their business ventures was a health shop, reminiscent of our parents’ original drogisterij.

When I left school my father asked me what I wished to do. The English language had more or less become second nature to me by then and I enjoyed writing and so I told him that I was interested in journalism. He called on the proprietor of the local newspaper who, though initially reluctant, agreed to employ me on a trial basis. After two years I began a cadetship with The Border Watch. I always loved my work there and remained on its reporting staff for ten years until moving to Adelaide after my marriage.

My husband Bill and I settled in the Adelaide Hills where we raised our four children. I never returned to paid work but found new and different ways to continue writing.

For my father a new job possibility arose with the establishment of a forest research station in 1964. To maximise his chances, he inquired about further studies in his profession and to this end obtained a declaration from the Netherlands Attaché in South Australia proving that he possessed a Dutch diploma which qualified him as a pharmacist-druggist.

At 54 he was considered too old for a permanent appointment but a friend with some connections put in a good word for him, writing to the local Federal MP about my father’s qualifications and enthusiasm for the work, and about the personal sacrifices our parents had made to give us a better chance because of the promise Australia had held out to hard working people.

He obtained a temporary job in the station’s laboratory and it was to be the one brief period in his life in Australia when his professional dignity was restored. He was happier than he had ever been since his arrival. Realistic about the temporary nature of the job though, he also began inquiring about work as an insurance representative. But in 1966 he was diagnosed with an inoperable malignant brain tumour. Even as he lay partially paralysed in an Adelaide hospital after his investigative surgery, he received a formal letter from the Forestry and Timber Bureau, advising him that his job had come to an end. He passed away in Mount Gambier on 30 January 1967, a day after his 57th birthday.

For my younger siblings further education became feasible through scholarships and the like and they all continued their studies in Adelaide, 500km from home. My younger sister, Rose, became a school teacher and throughout the years, wherever she lived, she also gave swimming lessons to youngsters. She and her husband, Greg, and their family would live and work in Tasmania and New South Wales before returning to South Australia. In a part-time venture, Greg turned his hand to woodturning and Rose used her artistic talents to apply colours to his platters and bowls. These became popular pieces of merchandise in a number of galleries in the Adelaide Hills region.

My youngest brother, Patrick, graduated in metallurgy. He then became a secondary school teacher and later an Education Officer with the South Australian Metropolitan Fire Service. Patrick then chose a career change and after seven years of part-time and full-time studies he became a chiropractor and today runs a thriving practice in Adelaide.

My brother Frank had a career in forestry and natural resources in South Australia and the Northern Territory. He died in Darwin in 2013, from a rare and aggressive form of cancer. The eulogies at his funeral brought home the impact that he had made as a driven and passionate conservationist. He was described as a true founding father of natural resources management in South Australia. As lecturer at Roseworthy College he had enthused pupils with his love of the environment and its flora and he retained a long term interest in them and their careers as they developed. He was said to have inspired many of the senior leaders in South Australia of today.

Frank had a special concern for conserving the Murray River flood plain in South Australia and to this end initiated the planting of over a million trees. In Darwin he spent ten years on a thesis in which he developed a holistic approach to the study of the natural environment and cyclones in particular. Frank received his PhD only months before his passing.

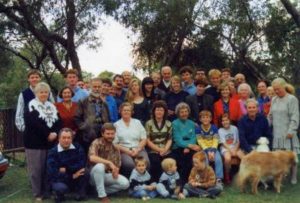

My siblings and I would all agree that over the years Australia has definitely become our homeland and we would no longer feel at home in The Netherlands. At the same time, we have never cut ties with our Dutch relatives and, except for my father, we have all returned to the land of our birth for visits over the years. None of us married a Dutch-born partner.

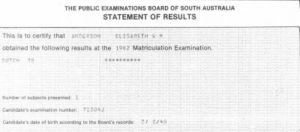

Personally, I still have an interest in the language and culture of my former homeland. It was re-ignited for me in 1982 when I attended an adult Dutch Matriculation class in Adelaide, conducted by a Helmond-born teacher, Trudy van Dyk. We conversed in Dutch, immersed ourselves in the rich history of The Netherlands, in science, literature, the arts and politics, and studied the 1957 wartime novel “Het Bittere Kruid” by Marga Minco. We wrote all our assignments in Dutch. This proved to be an interesting and stimulating experience.

Recently I have been involved in the assembling of stories about Dutch migrant families who settled in the South East of South Australia after World War II. I feel a great affinity with the people who have shared their experiences for this project and I am pleased that their stories will no longer be left untold.

My mother was widowed for 33 years and nine months. She continued to live in our Mount Gambier home and died there on 20th October 2000, aged 88. The photographs and memorabilia which she always treasured became my main source for a comprehensive family history, completed in 2011. The book bears the title “A Cloth Well Woven”. This was inspired by a colloquial Helmond expression, “hij heb seen lapken goed afgeweve”, used to describe a person who has come to the end of a well-lived life. I felt that it was appropriate for my ancestors and for my parents who had given of their best.

I was pleased to also devote a page to the story of another van der Sommen family, distant relatives in Perth who, to our very great surprise, had made contact with us in their own search for their ancestry.

In 2014 my parents’ descendants number 41, spread over four generations.

- Written by: Elly Anderson, 2014

- Funded by: Your Community Heritage Grants, The Department of the Environment, Canberra.

- Interview Series 2014: organised by Dr Nonja Peters, History of Migration Experiences (HOME), Curtin University, Perth Western Australia.