Adriana Taylor, from Dutch Schoolgirl to ‘Servant of the People’

It is normal for the eldest son to inherit the farm. This has been true over the centuries, and in many places in the world. Jos (Adrianus Johannes Ansems), known to all as Lange Jos, refused the privilege. He had no heart for farming after a childhood of helping out, especially when the weather was cold, and chose to be a bricklayer in the nearest big town, Tilburg.

Before the second world war, bricklayers had the opportunity to practise their trade as a craft, and their work still remains as a testament to their skill, work that can be admired. However, the lot of a bricklayer in the Netherlands is not a completely happy one. Working in winter is painful if it is at all possible. The cold makes bricks hurtful to handle, and the mortar that binds the bricks together is reluctant to cure.

Jos became tired of the cold, and began to long for warmer climes. He thought South Africa might be a nice place to live, and perhaps Australia too. So he applied to migrate with his family to both countries. Australian officials were quicker in processing his application, and so it came to be that Jos Ansems and his family arrived in Melbourne in February 1956.

Mum Dien, (Huberdina Cornelia Bayens), came in fear and trepidation, leaving behind all their extended families, with no knowledge of the English language or Australian customs. Her eldest daughter, Nettie (Antonetta Adriana), was 17. She had just begun work, and was now broken-hearted because of the boyfriend she had had to leave behind. He had wanted to come too, but was persuaded, with the promise of a new bike, by his mother to stay.

The only boy in the family was Frits (Godefridus), then 15 years old. He also found the transition hard, because he had been yanked from being a school boy active in Judo and Soccer, and a safe circle of teenage mates. Now he was in a strange country, with no prospects of further education and the need to find an unskilled job.

For 9 year old Adriana (Adriana Antonetta), migration was pure adventure. Life on board ship was exciting, with lots of other children to play with, lots of food, and no school. Besides, there were exotic places enroute to see – the Panama Canal and Tahiti were especially memorable. They hadn’t planned it this way, but the Suez Canal was closed because of a political crisis.

The family had no relatives, friends or sponsors in Australia, and were thus sent to the Bonegilla migrant processing centre near Albury. Adriana loved the freedom and the warmth, but her mum suffered dreadfully from the inland Australian heat and insects that first summer.

Jos travelled on to Sydney to work on the railways, and Frits followed, together living at the Villawood Migrant Camp—the girls made the family complete again after a couple of months. Jos had little choice in work because his qualifications were not recognised in Australia. The unions here had contrived, by the mid 1950s, to close the door to skilled work for migrants for fear of losing their places to newcomers prepared to work hard for long hours. Despite this rejection, he was determined to become an Australian as soon as possible. After working in various jobs, Jos eventually became a cleaner in Sydney cinemas. The hours allowed him time to deal in scrap metal, first as a hobby, later as a full time living, allowing him eventually to travel the outback of Eastern Australia, a country he grew to love dearly.

The youngest daughter was sent to the nearest catholic school, Sacred Heart in Cabramatta. This working class suburb of Sydney had become a microcosm of urban Australia because of its proximity to Villawood.

Adriana began her Australian schooling in July 1956, not knowing a word of English. During the next few months, the Dutch “cupboard” in her mind closed, and she learnt sufficient English to finish the year third in class. She had reached a point where even knowledge of the Dutch cupboard became a very dim memory.

Adriana began her Australian schooling in July 1956, not knowing a word of English. During the next few months, the Dutch “cupboard” in her mind closed, and she learnt sufficient English to finish the year third in class. She had reached a point where even knowledge of the Dutch cupboard became a very dim memory.

The family’s first independent home in Australia was on a houseboat moored on the Georges River at Carramar, still in the same area. Tragically, that next summer, the houseboat sank and with it most of the very few treasured possessions the family had managed to bring with them from the Netherlands.

The family found new accommodation nearby, in a detached unit belonging to an Italian family, sharing an outside toilet. Jos became known as Adrian, Frits became George and Nettie changed to Toni, to fit better within their new society. All three of them went to work and Mum, an accomplished seamstress, took in sewing.

A year after arriving in Australia, Adriana’s mum became sick. When it was finally determined that she was ill with typhoid fever, it was too late to treat her, and she died, only 54 years old. Several years later the two eldest children had moved out of the family home, and Adriana was often alone. Her father had determined to be an Australian despite a heavy accent which he never lost, and so not to associate with any Dutch clubs or groups. He was now almost 60 years old, with odd working hours and not quite the company a teenager desires. Relief was, however, at hand.

Access to education scholarships was open to all, including migrant children, whether naturalised or not. Adriana succeeded in an application for a half scholarship at St. Vincent’s College, Potts Point for the final years of her education. A separate two year cash scholarship from the Lidcombe Mens’ Working Club provided money for the College boarding fees. Doing her best and working hard saw Adriana graduate as Dux of the College in 1963. At the 50-year reunion, she renewed many of the lifelong friendships made in those years with boarding students from all over country New South Wales.

The final years of her education were essentially ‘living in’, and ‘living in’ meant something vital to her life which was not available elsewhere – it meant being part of a group. There is, of course, no point in being part of a group unless joy, as well as support, can be found there. For Adriana, the strength and comfort of a group came from exercising a servant attitude, choosing to use her time and talents to look after number one. The real trick is to remember that it is everybody else who is number one. When all members of the group play the game this way, all members are equal first, and all get from the group the things they most need and lots more besides.

It was for exactly this reason that Adriana, armed with a Commonwealth Scholarship, chose to apply for entry to the University of New England – this institution also had ‘living in‘ facilities. Here she focused on an Arts degree, majoring in Australian and European History. It was also here that she met a man called Beres Taylor. After graduation, they both managed to get teaching positions at St Mary’s College in Gunnedah – history for her, maths and science for him. It was also in this town that Adriana Ansems became Adriana Taylor, and they lived happily ever after. We cannot, however, finish the story there, as there is much yet to tell.

After three years, the couple went to live in Sydney, but as a country boy, Beres was never comfortable there. He took a job in a bank rather than in teaching because it promised to pay more, but that didn’t improve his humour. A visiting friend told them about Marist Regional College, in Burnie. Their interest piqued, they visited, and were impressed. Even better, they both gained teaching positions there. Moving into a more relaxed, friendly Tasmanian community is a step they have never regretted.

There was, however, a small cloud on the horizon. They both saw that their qualifications could be improved to strengthen their position or improve their career prospects. Reluctantly, after two years, they moved to Hobart, and went back to university. Beres finished his science degree, and Adriana did a Diploma of Education. This was paid for by a scholarship from the Education Department, but this scholarship came with strings attached. As soon as her Diploma was earned, she was posted to Risdon Vale Primary School. For the first time in her life, she was outside the Roman Catholic education system. This was inconsequential, she was happy to be teaching again after the study break, and particularly happy to be teaching in a low socio-economic area where she felt she could make a difference.

Daily life was, however, a little awkward at this time, because the Tasman Bridge had been partially demolished by an errant freight ship just before the first school term commenced. It forced a long daily commute, a time and energy waster, though it did give time to build strong relationships with fellow travellers.

The following year Adriana and Beres decided to stop renting and moving about, and to buy a property in the foothills of Mount Wellington at Collinsvale. It was an old farmlet, and it has served them well. The old farmhouse needed some modifications and repairs, which were mostly done by Beres as he discovered an affinity for working with his hands. Those same hands also made beautiful pottery, as a hobby. When he retired, Beres made quite a lot of pottery, but eventually had to stop because his back couldn’t cope with being at the wheel. Since then he has discovered the joy of working with Tasmanian specialty timbers, particularly Huon Pine.

In their first year on the farm, the couple were blessed with a baby boy, Patrick, and in the following year with a second son, Steven. Adriana stayed at home – initially as a stay at home mum, and later to give the boys home schooling. This continued until the boys were ready for upper primary school, at which point the boys went into the Catholic education system. Adriana then changed from being their teacher to being their taxi driver, bringing the boys to school, and to after school events, and to sports on Saturdays.

Staying at home with the boys in those years (late 1970s to mid 1980s), Adriana realised she had more to give than the boys needed. She and Beres decided that the house and property were big enough to share with others should the need arise, and from time to time it did. Their home thus became an occasional retreat for people who needed time out, a break from the routine or a haven from a bad home situation. It also became a place for more organised, yet still ad hoc, events such as days of communal prayer.

It was in this post-Woodstock era that the cry for love and peace became practical urges for growing your own vegetables moreover, if you had the space, to have chooks and other productive animals and fruit trees as well. Everything had to be organic, free of all the chemicals that modern industry insisted was at least okay and probably even good. Self sufficiency was the holy grail. Common phrases in these years were ‘hippy‘ and ‘earth mother‘ to describe the lifestyle, but this status was never Adriana’s or Beres’ intention. If they did attain this status it was something that happened along the way. What was important was to have a property and use it for people who needed sanctuary and time out.

This was a healing ministry – good for the host, the guest and the earth of which we are all guests.

It was in these years that Adriana and Beres also found themselves increasingly involved with local organisations. Working for the community in voluntary positions was, they found, quite rewarding. Collinsvale is not a big town by any definition, so the pool of volunteers is never large enough for the things that need to be done, the things that help a community of people bond. There was the Fire Brigade, the Hall Committee, the CWA, and Parish Council.

Reviving the Collinsvale Show and managing it for ten years, and many other worthwhile causes, all without a mobile phone, kept the family very busy. Adriana was singled out for recognition of effort and achievement by the Glenorchy City Council and made Citizen of the Year in 1987.

During the stay at home years there was also a reminder of the past. Since the early death of her mother, the family had long ago lost touch with their Dutch relatives, but an elderly maiden aunt, of whom she knew nothing, had willed some money to her and her siblings. A solicitor had duly tracked her down, which meant that she did get a very small inheritance, but also that they re-established contact with their extended family in the Netherlands.

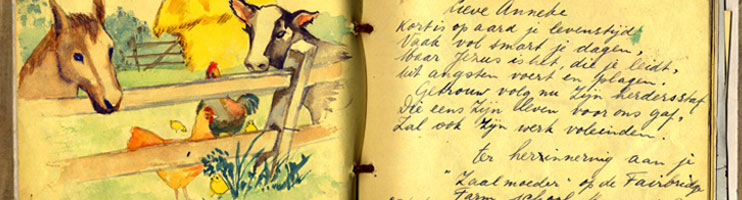

An uncle and aunt subsequently came to visit, albeit only as far as Sydney. Adriana therefore travelled up, and was also able to stay with her sister. She was a reluctant traveller, as she was convinced that communication with the long lost family would be very awkward. Dutch people of her uncle and aunt’s vintage generally have little or no English, and Adriana thought her Dutch was long lost. Within 24 hours, however, the Dutch cupboard in her brain opened, but it contained all the banter and idioms of the 1950s, no longer used. Thirty year old phrases spilled into the room, to the delight of the visitors.

Aware now that her language skills were available, a trip to the Netherlands was planned. In 1989, with a friend, she travelled to England. She thought that being in a foreign country where English was spoken might accustom her to the concept and practicalities of travelling. In reality she found England drab, and the people difficult to understand.

The original family home, although the attic room has been enlarged since the family migrated.Holland, on the other hand, was the complete opposite. Her fear of being unable to understand and or communicate evaporated upon arrival. Holland was home. The landscape was familiar – green, flat, with regular rows of trees – just as in her childhood. Some roads were now wider and more straight, and the towns were bigger, but the town centres were much the same and full of life, with markets and people sitting outside cafes, even when the temperature was barely in double digits.

It was not just the language but the way people interact, their relationships, their behaviour in public and private. She found her natural social skills, like talking to strangers in the shop, to be normal behaviour. The same behaviour in Australia was seen as too frank or clumsy or awkward, even wrong.

After becoming Citizen of the Year, some of the senior councillors of the Glenorchy City went to see Adriana because they thought she would be an ideal candidate for Council. They thought that if she could be elected, the matters of the city would be in capable hands, and they could retire. Adriana was reluctant to agree because she had never aspired to political office, and had little money to spend on a campaign. She agreed on the condition there would be only one shot, one try, for office. There would be no try and try again until success was achieved.

The campaign budget allowed for little more than some A3 black and white photocopies to do the job of posters, and some string to hold her shoes together, literally and figuratively, (only a small exaggeration). This didn’t bother the voters, and Adriana was duly elected in March 1999. Their confidence was rewarded with her honesty, credibility, and concern for the welfare of her fellow citizens. She was recognised as a servant rather than a self seeker, or a self promoter. At the next election she was again chosen by the people to serve them, but this time as Lord Mayor of the City of Glenorchy.

All of her work as a volunteer for community organisations had made her keenly aware of the scarce resources available to them. This inspired her to push for a volunteer centre where resources such as computers and photocopiers and the like were available for a nominal charge. Any help was good because she knew that volunteers play a key role in the health of a community.

However, before her third term as Mayor was complete, she was again put to the test. At the request of many, she agreed to stand for the Legislative Council seat of Elwick. Applying her talents and organisational skills, and her concern for the well being of the voters in her electorate, would not be difficult. The dilemma was that her term as Mayor still had 16 months to run.

It was calculated that the cost of a by-election for a new Mayor would be in the order of $100,000. Adriana figured she could, for 16 months, perform both tasks, and thus save the ratepayers an unnecessary burden.

However, she would not draw two salaries – one was sufficient, and so she resolved to use one salary to the benefit of newly set-up charity, The Glenorchy Community Fund. The electors chose Adriana to represent them in the State house of review, the Legislative Council, in March 2010.

As a student, a teacher, a community volunteer, an alderman, or Lord Mayor or Legislative Councillor, Adriana has always had an eye to the group, an eye to find practical ways to improve the life of her fellow-man. Her work has always been marked by a servant attitude, with a hands-on approach. There has never been an inkling that her public or private work has been motivated by an urge for reward, whether in this world or the next. At every stage of her life she has had the quiet knowledge and satisfaction that she has done the best she can to make this world better for other people.

- Collated by: Kees Wieringa, 2014.

- Funded by: Your Community Heritage Grants, The Department of the Environment, Canberra

- Interview Series 2014: organised by Dr Nonja Peters, History of Migration Experiences (HOME), Curtin University, Perth Western Australia.