Dutch diaspora to Australia

Dutch diaspora to Australia

Since 1606 the Dutch have at various times had strong maritime, military or immigration connections with Australia. The focus of this history is the period from 1947 to 1970, when the Commonwealth Government deliberately set about enticing emigrants to Australia for security, to reverse population stagnation, overcome crucial labour shortages, restore essential services to pre-war levels and maintain the war-boosted economy. Prospective emigrants were enticed to come with promises of materialism inaccessible in post-war Netherlands plus passage assistance. All that was required of a prospective emigrant was that they meet the White Australia policy-governed entry, age and health criteria and remain in the type of employment for which they were selected and wherever Australian authorities sent them – for two years.[1] Concurrently, they were encouraged to leave by a Dutch government and Monarchy not in a position to offer them either appropriate sustainable employment or housing.

The Dutch diaspora, between 1949 and 1970, a direct consequence of World War Two, saw an estimated 70 per cent of the 160,000 Dutch nationals seduced into leaving everything familiar behind to start a new life in a strange new world, eventually commit to permanent resettlement in Australia.[2] At the 2006 Census, largely as a result of natural attrition, the number of Netherlands-born Dutch still resident in Australia had reduced to 78, 260 (ABS 2006).[3] The distribution, by state and territories, show that Victoria continues to have the largest number with 22,830 followed by New South Wales (18,820), Queensland (15,260), Western Australia (10,110), Adelaide (8,500) and Tasmania (3,000).[4]

These reduced numbers have not, however, diminished the Dutch presence, given that at the 2006 Census nearly 300, 000 Australians claimed Dutch heritage.[5] Approximately 60 per cent of Dutch entered Australia under assisted passage schemes – Allied Ex- Servicemen’s Scheme, Netherlands Australia Migration Agreement (NAMA); Netherlands Government Agency Scheme (N.G.A.S). The remainder were full-fare paying.[6] However, because passage assistance was means tested and emigrants were restricted in the amount of cash they could take out of the country, the majority of Dutch migrants – assisted and fare paying – arrived in Australia without financial resources. That is apart from landing money, which in 1950 was £10 for singles and £20 for a family. The dramatic devaluation of the rupiah similarly reduced resettlement possibilities for Dutch Nationals from Netherlands East Indies (NEI).

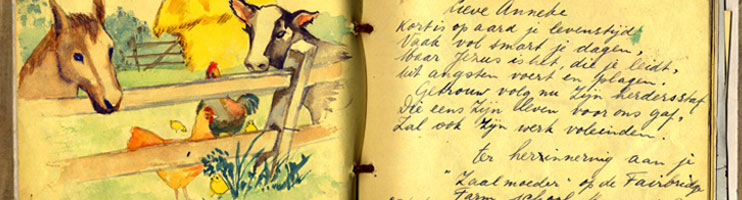

Practicalities, inveiglement and inducements aside, few Dutch emigrants were really aware of the psychological and physical complexity an emigration undertaking would engender. Moreover, not many felt that the expectations promised by the receiving society were delivered, at least in the initial years following arrival. One of the key lures – a house of one’s own – was probably the biggest disappointment. For as it turned out, Australia’s housing situation was hardly better than the one they had left behind. When they arrived Australia’s residential stock was down by at least 300,000 homes due to lack of material and expertise. Besides, they were never warned that owning a home of their own would entail building it themselves! Nor did most perceive (until it was too late) that the migrant camp accommodation on offer, on arrival, would be so austere. Located mostly in unused military barracks in the countryside, these institutions proffered only basic comforts and little privacy. As for a vehicle and whitegoods, generally, migrants started with a motorbike or drove a variety of ‘old jalopies’ until they had saved enough to purchase a new model sedan or utility, which often took years. They could purchase ‘white goods’ on hire purchase providing they could service the loan. This was however, dubious given the high cost of even dilapidated rentals, which in better times would have attracted a demolition order. Moreover, they needed to save for a block of land and to buy cement to make bricks for their house. In the 1950s, migrants had to get the house to ‘plate height’ (ready for the roof to go on) before they could access bank finance to finish it.

- selling a dream – expectation versus reality: Post-war and other migration to Australia 1945- 1970

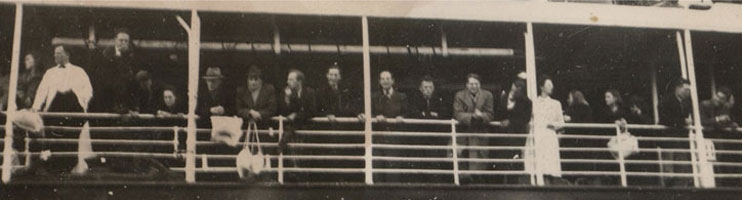

- searching the shipping lists at the National Archives of Australia

[1] Nonja Peters, Milk and Honey But No Gold: Postwar Migration to Western Australia 1945-1964 (Perth 2001).

[2] Netherlands-born Historical Background, Community Information Summary, Australian Government Department of Immigration and Citizenship. (http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/comm-summ/source.htm)/: The Dutch Nationals included people from the Netherlands and approximately 10,000 from the Netherlands East Indies.

[3] Nonja Peters (ed.), The Dutch Down Under 1606-2006 (Perth 2006).

[4] Netherlands Community Profile, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Catalogue No. 2001.0, Commonwealth of Australia (Canberra, 2002): In approximate numbers, most first generation post-war Dutch settled in Melbourne (33,000) and Sydney (30,000), followed by Brisbane (17,000), Perth (12,500), Adelaide (9,000) and (3,500) in Tasmania, where they are the largest ethnic group.

[5] The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census of Population and Housing Catalogue (Canberra 2006).[6] R.T. Appleyard, ‘The Economic Absorption of Dutch and Italian Immigrants into Western Australia 1947 to 1955’, R.E.M.P. Bulletin 4:3 (1956), 45-54, 48,49.